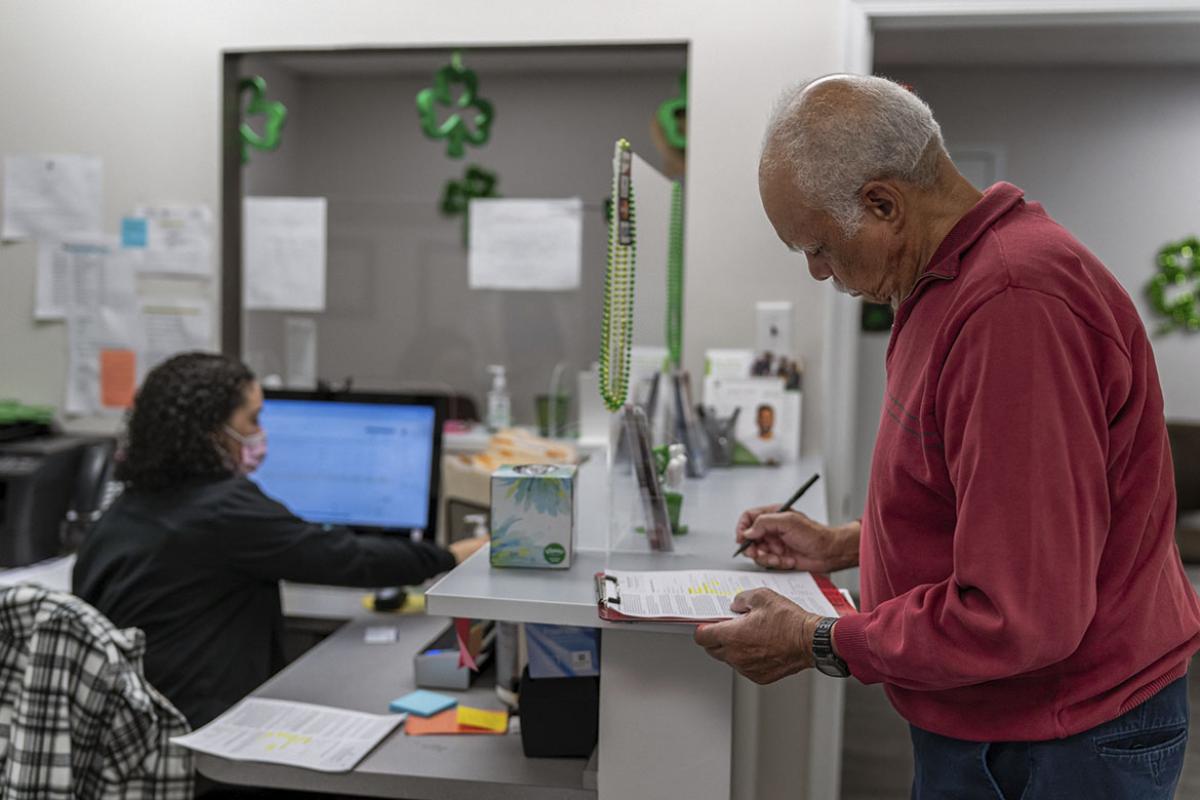

At some point during medical school, nearly all students will encounter standardized patients, also referred to as simulated patients. Standardized patients are trained to portray realistic encounters in which medical students can get key experiences that focus on both clinical and communication aspects of medicine.

Now a first-year ophthalmology resident physician at Johns Hopkins Wilmer Eye Institute, Whitney Stuard Sambhariya, MD, PhD, encountered standardized patients in both the preclinical and clinical phases of her medical school training. During clinical training, standardized patients were frequently used during end-of-rotation Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs).

Looking back on the way she worked with standardized patients, Dr. Sambhariya as a medical student at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, Dr. Sambhariya spoke of how beneficial these interactions were to her growth.

“If I could go back, I would really focus on the communication component of standardized patient interactions because there is so much you can learn and gain from them,” she said. “Oftentimes, in medical school, students spend so much time and energy focused on the clinical aspects. For example, what diagnosis may someone have if they are exhibiting symptoms X, Y and Z. But there is so much a student can benefit from by just talking to the patient; I didn’t realize at the time how important just interacting with people would be in my career.”

For students preparing to work with standardized patients, Dr. Sambhariya offered guidance, reflecting on what she would have done differently during this part of her medical training.

Master the art of conversation

“Now, if I work with standardized patients—which we've actually gotten to do in residency—I focus a little bit more on: Was my interaction fluid? Did they feel that I was able to establish rapport? Do they feel that I was able to ask questions and make them feel comfortable with giving me the answers and telling me their story?” Dr. Sambhariya said, “Being able to establish those things is so important. While someone may know the question to ask, if you don't foster trust and a safe, accepting environment with your patient, they may not answer the questions fully and key information may be lost.”

During medical school, “we had a particular standardized patient encounter where the focus was on having difficult conversations. I didn't realize how beneficial these experiences were and how much I could learn from them. I now recognize that those conversations I practiced in medical school are the ones that I am having with people every day,” she added.

“I just think I would have slowed down a little bit, tried to really absorb more of the feedback that I got from my standardized patients, and asked some more questions—even if the question is just asking what else I could have asked. I don't think I knew at that point all of the things to ask.”

Dr. Sambhariya highlighted that one of the goals of standardized patients is to develop “social skills, figure out what kind of questions you need to ask, learn to establish empathy and rapport during what may be a very probing interaction, and acquire skills in having tough conversations.”

Body language matters

“Work on your own body language, make sure that you are making eye contact with the person,” Dr. Sambhariya. “That's just a good life skill in general for all of us to continually work on—making sure that you are actively listening.”

“I make sure I nod my head, uncross my arms, and keep my shoulders open. For younger patients, I try to sit down because they are physically smaller, and I do not want to tower over them. I want them to feel comfortable enough to share information with me, so that I can treat them with all the facts,” she said. “I also try to pair my body language with responses to further elicit more information, such as ‘Can you tell me more about that? How did that make you feel? What happened after that? When someone shares difficult information with you, you have to respond and reflect in a way that shows you are paying full attention.

“For example, ‘that must have been very hard.’ These short sentences can help the patient recognize that I am present, fully engaged in the conversation and that I want them to keep telling me their story,” she added. “Active listening, facial expressions, body language are all important to developing a better relationship with your patient—and getting to the diagnosis faster.

“The more practice you get with talking with people the better. Most of our medical students have the knowledge base. They've been in class for years. But applying it when you're talking to a real person can sometimes be a little overwhelming and it can be difficult to pull from that fund of knowledge—to roll with the story that you’re hearing and go with the flow—I think that's a big thing that our students, and I, had to learn.”

Treat it like the real thing

“Go into each standardized patient's encounter acting like it is a real patient: Say this is real, this is what this person is going through, and ask yourself, 'how would I expect this person to feel in real life?’ That helps with being able to really exhibit empathy,” Dr. Sambhariya said.

Sometimes, she noted, “it can be challenging to take the standardized patient presentation with utmost seriousness, yet doing so is a must and “one of the best things to do because you can learn so much from each encounter. The implementation of the feedback shapes how you face patients in the future.

“A lot of the standardized patient interactions are funny. They'll say, ‘Oh, my leg is swollen or bleeding,’ and have it wrapped up in a giant bandage you can't take off because it's not actually bleeding or swollen, and you use some imagination. It’s important to try to treat it as a real scenario because you're going to have those patients [with these actual conditions] someday.”

Understand expectations

During standardized patient encounters, faculty members are there “looking for students to demonstrate their knowledge of different diagnoses,” Dr. Sambhariya said. “You are expected to start with a laundry list of possibilities of what could be the cause of the symptoms, then to formulate a plan and narrow the possibilities, and ask the correct questions. You have to go with the flow because as you're getting new information, you will need to alter your plan to figure out what you are going to do next.”

“They're looking for interpersonal communication skills, whether that's how you're speaking to a patient, how you are using your body language, how your bedside manner is, and making sure that you've learned how to treat a patient—with politeness and respect. All of which help you develop rapport.”

Solicit, apply feedback

“These sessions are often recorded, so students could go back and watch themselves and say ‘OK, what was awkward about that scenario? How can I fix it next time?’ Those videos are very important and can really teach you a lot about yourself and how you appear to others,” Dr. Sambhariya said.

“Have other people also watch your videos. A lot of us have mentors in medical school. They can be a great source of feedback and can be really beneficial,” she said. “For example, at my medical school we were in small groups with a mentor. The mentor would watch our videos and give third-party feedback.”

Such mentors also can help medical students find moments during the encounter when they missed opportunities to offer empathetic comments or probe further and help sharpen “their communication skills and style,” Dr. Sambhariya said. Overall, “having multiple opinions” on such encounters is valuable.

“Everyone communicates a little bit differently in medicine,” she said. “Having other people give you feedback on your techniques and communication skills—what you can improve, what you can change—is important and necessary for improvements.

“Standardized patient encounters are a good time to make mistakes and learn from them. It is a hard thing when you get into residency and now, you’re the one having these difficult conversations with patients,” Dr. Sambhariya added. “You're the one telling a patient about their cancer diagnosis. Those conversations do come up. Standardized patient encounters can prepare you for these situations and give you the confidence you need to walk patients through these hard conversations.”

"We're all continually learning. We're all—always—learning new techniques to help us communicate better and more emphatically. But standardized patient encounters are a great starting off point to prepare you for the real world, namely residency.”